In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should:

- Understand the importance of assimilating evidence when deprescribing medication

- Be aware of the attendant legal and bioethical issues

- Be familiar with GPhC guidance for pharmacist prescribers.

Key facts

- A patient was prescribed ramipril for high blood pressure by her GP

- Subsequently, she purchased Wegovy and, having lost weight and reduced her BMI, her blood pressure has fallen

- The patient asks you if she can stop taking her antihypertensive medication.

Imagine the scenario. Jackie is a 36-year-old accountant. She has a BMI of 33 (180cm tall and weighs 108kg), is a moderate smoker (up to 20 cigarettes a day) and drinks around three glasses of wine each day but rarely exercises. She has a history of migraines and usually manages these with Migraleve tablets.

Following a visit to her local pharmacy for a blood pressure (BP) check, this was found to be 150/95mmHg. Subsequent ambulatory daytime monitoring revealed levels ranging from 135/85mmHg to 149/94mmHg.

After referral to her GP, Jackie was initiated on ramipril 5mg daily. She was reluctant to take any treatment and after seeing a social media video on the benefits of Wegovy (semaglutide), she decided to order the drug online.

Blood pressure review

As an independent prescribing pharmacist working alongside a GP practice, you have been asked to see Jackie to review her antihypertensive treatment. She informs you that she took Wegovy for a total of nine months but has now stopped. At the clinic today, her BP reading is 124/82mmHg and her BMI has reduced to 29.3.

Having lost weight (she is now 95kg) on Wegovy, Jackie has become highly motivated. She has stopped smoking and started going running most mornings as well as lifting weights at the gym. She now wants to stop her ramipril. How should you respond?

Assimilating all the evidence

At the present time, Jackie’s blood pressure has returned to normal levels which, according to NICE, should be <140/90mmHg. On the face of it, it would seem sensible to stop Jackie’s ramipril, but deprescribing antihypertensives does raise several important considerations.

Available guidance

Guidance from the General Pharmaceutical Council (see further reading) states the following: “Pharmacist prescribers are responsible and accountable for their decisions and actions. This will include when they prescribe or deprescribe, and for their prescribing decisions.”

It also says: “Pharmacist prescribers must make sure their prescribing is evidence-based, safe and appropriate. Any prescribing decisions must be made in partnership with the person being assessed, to make sure the care meets their needs…”

As a prescriber, you would therefore need to consider whether or not it is both safe and in the patient’s best interests to deprescribe the ramipril. However, before making any changes, there are significant clinical issues to consider.

Is it safe to deprescribe?

From an NHS perspective, deprescribing would make cost savings by stopping unnecessary treatment. Now that Jackie’s BP is within the acceptable range and she has lost weight, this would seem the most sensible thing to do. How this process should be undertaken is far less clear.

Most guidelines focus on initiating and increasing the dose of antihypertensive therapy, offering little, if any, advice on deprescribing.

NICE simply states that withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs should occur gradually, over a two- to four-week period.

In contrast, the Summary of Product Characteristics for ramipril says that “abrupt discontinuation of ramipril does not produce a rapid and excessive rebound increase in blood pressure”.

This lack of any clear direction means that clinicians are often very reluctant to stop treatment, unless the patient is experiencing adverse effects.

One suggestion for deprescribing antihypertensives is to halve the dose or take the ramipril every other day. But how likely is it that Jackie would remain normotensive if her ramipril were to be stopped?

Some evidence to answer this question comes from a review of antihypertensive withdrawal in 2017. Researchers found that after one year, 40 per cent of patients remained normotensive, although this dropped to 26 per cent after two years. Predictors for successful withdrawal included monotherapy, a lower BP before withdrawal and possibly a lower body weight.

A further consideration is whether there is evidence of end-organ damage and an individual’s overall risk of developing cardiovascular disease over the next 10 years.

Since Jackie now has a lower BP and has lost weight, her QRISK3 score is only 2.4 per cent, suggesting she has a very low risk of developing cardiovascular disease in the next 10 years.

Why did her BP fall?

Was it weight or semaglutide that caused the reduction in Jackie’s blood pressure? In short, the answer is both.

According to a 2021 updated Cochrane review of eight randomised controlled trials in 2,100 patients with primary hypertension, while reducing body weight, weight loss diets also produced a small but significant reduction in BP.

The mean decrease was 4.5mmHg for systolic pressure and 3.2mmHg for diastolic. However, an important caveat was that the true magnitude of the effect was uncertain because of the small number of participants and available studies.

Although a recent systematic review of six randomised controlled trials with 4,744 patients concluded that semaglutide treatment reduced both systolic and diastolic blood pressure by an average of 4.83mmHg and 2.45mmHg respectively, this was only assessed in normotensive patients.

Nonetheless, another analysis with more than 3,000 patients found that semaglutide gave rise to reductions in systolic blood pressure of between 3 and 4mmHg, although diastolic values were not reported. Interestingly, there was also some evidence that deprescribing of antihypertensives occurred in those co-prescribed semaglutide.

While this data indicates that semaglutide may have been responsible for some of the decrease in Jackie’s BP (in conjunction with her weight loss), it is important to remember that she is no longer using semaglutide.

There is evidence from a study in which semaglutide was stopped indicating that one year after withdrawal of semaglutide and lifestyle interventions, participants regained two-thirds of their prior weight loss.

Legal issues

It is legally recognised that deprescribing has the same status as prescribing and therefore requires the necessary clinical expertise to recommend that a medication can be withdrawn and that this is for the benefit of the patient.

Given the lack of clinical guidelines to support deprescribing, it might feel daunting to consider stopping a patient’s medicine. Could deprescribing actually expose a prescribing pharmacist to possible litigation?

In general, litigation only arises when there is evidence of clinical negligence. Normally, a healthcare professional will be open to a claim of clinical negligence in cases where their actions fall below the reasonable standard of their peers.

In order to prove that a prescribing pharmacist is negligent, it is necessary to establish that no other such pharmacist with the same qualifications and expertise would have acted in the same way when faced with the same circumstances.

A further consideration for judging clinical negligence is any current standards or guidelines related to the action. In other words, did the prescribing pharmacist follow accepted guidelines on deprescribing ramipril?

In the absence of firm guidelines, the pharmacist is potentially liable if the patient experienced subsequent harm, such as a stroke. There is also a need to satisfy the criteria of informed consent.

Jackie needs to be made fully aware of any material risks associated with the deprescribing of her ramipril, however small those risks.

In summary, if deprescribing becomes more common, prescribers who don’t consider this as an option or who fail to advise patients of any potential benefits may expose themselves to clinical negligence claims.

Prescribing pharmacists therefore need to discuss with their patients the risks and benefits of continuing a medication, together with the options for deprescribing.

While there is some guidance on deprescribing antihypertensives, there is a paucity of information on stopping antihypertensives for patients such as Jackie. Nevertheless, in the absence of such guidance, the practice should be undertaken only in partnership with the patient.

Bioethical issues

1. Beneficence: the core principle here is that the pharmacist needs to act in the patient’s best interests. The ramipril was prescribed to control her blood pressure. However, now that her blood pressure is within the normal range, it would seem sensible to deprescribe the ramipril, as this is acting in her best interests

2. Non-maleficence: avoiding patient harm is paramount and, in this case, deprescribing would help to reduce any harm associated with the use of ramipril. However, while there are several recognised potential adverse effects from taking ramipril, Jackie has not reported any of these.

Despite this, there is a risk that deprescribing the ramipril could lead to harm as a consequence of uncontrolled hypertension

3. Respect for autonomy: it is equally important to recognise the rights of the patient and to ensure that they are in a position to make an informed choice about their treatments

4. Justice: in the present scenario, who would be affected by your decision to deprescribe ramipril? By failing to cede to Jackie’s request, there is a risk that because she is aware that her blood pressure is now under control, she may decide to stop taking the drug without your approval and this might negatively impact the control of her blood pressure.

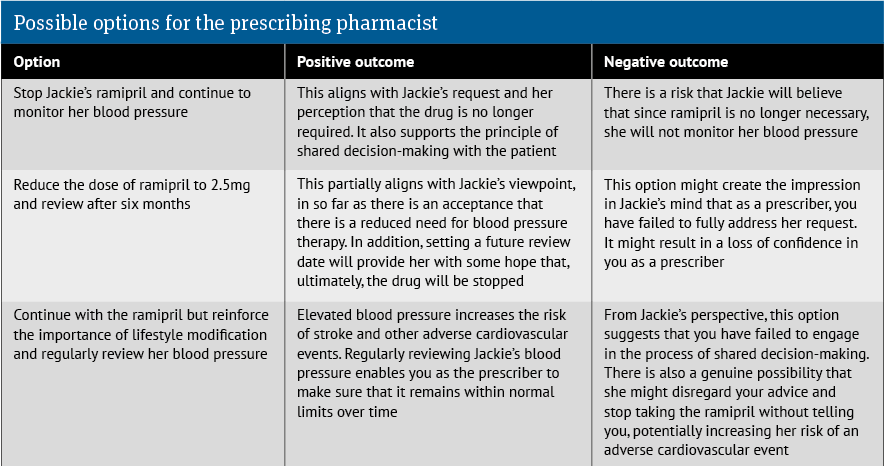

The possible options together with potential positive and negative outcomes are outlined in the table above.

What is the most appropriate option?

Although there is no one correct answer in this case, it would seem sensible for the pharmacist to deprescribe Jackie’s ramipril.

The prescribing pharmacist still has a duty of care to Jackie and must gain her informed consent, based on a full discussion of any possible risks associated with stopping the drug.

Nevertheless, it can be argued that because her blood pressure is now within normal range, and she has a very low risk of developing cardiovascular disease based on her QRISK3 score, ramipril is no longer necessary.

The prescribing pharmacist in deciding to deprescribe ramipril should also seek to reach an agreement with Jackie that she attends scheduled appointments, either at her GP surgery or her local pharmacy, over the next few months for regular BP monitoring.

Further reading

- General Pharmaceutical Council. In practice: guidance for pharmacist prescribers: assets.pharmacyregulation.org/files/2024-01/in-practice-guidance-for-pharmacist-prescribers-february-2020.pdf